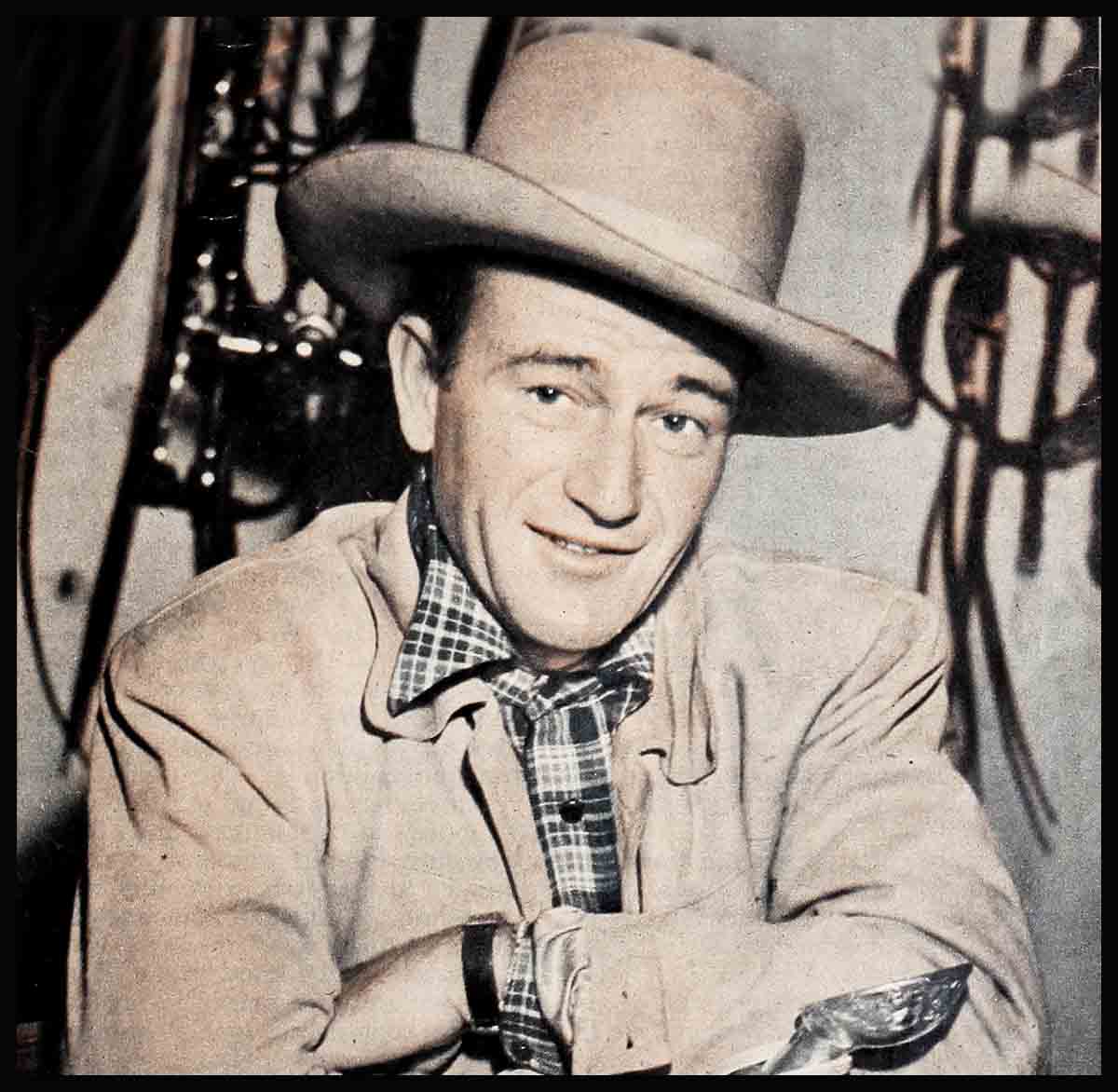

John Wayne The Duke

In the beginning, it is essential to remember that this fellow named Marion Michael Morrison—this six-foot-four ex-football star whom you know and like to watch on film as John Wayne—is still no more than a good Joe who fell into the ways of Hollywood, got famous, made a lot of dough and is a little astonished, even at this late date, that it all happened.

Today he is at a moment in his life which is supercharged with crisis, change and melodrama. Separated from his bride of ten years and from the four children to whom he has been such a devoted and sympathetic father these past years, he will probably join either the Army or the Navy within a few months.

This, at a time when his stardom is established, when two successful pictures—one co-starring with Jean Arthur—are cleaning up under his name, when every studio in Hollywood is scratching at his door, waving contracts.

To borrow him for “Reap The Wild Wind,” Paramount once had to guarantee him top billing over its own people; now, there is no longer any question about his billing, nor about the salary he demands. It is the time, of all times, to observe John Wayne closely, to listen as he ticks, to put him under a glass and judge from the personality revealed there what his eventual future will be.

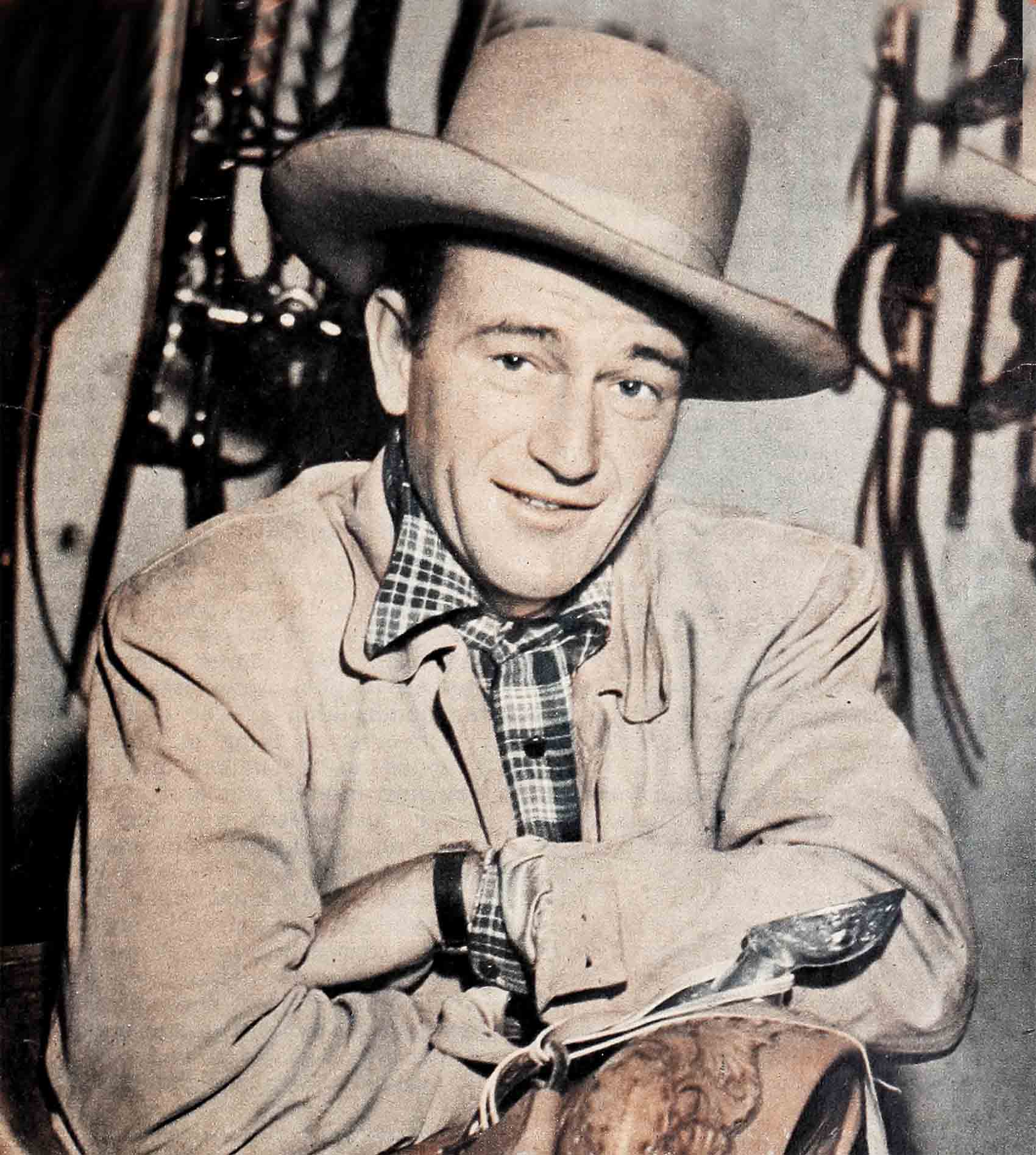

Everyone on the set and off calls him Duke, since he’s the kind of man who must be known by an affectionate nickname and that, held over from high-school days, is his. He gets along best with other men, although any woman in any room with him will do her best to thwart his preference; he is personified by such things as leather jackets, pipes, big bounding dogs; gymnasium shower-rooms, poker, camp beds, barbershop quartettes and the smell of horses.

Yet he is curiously fastidious. He looks well in dinner clothes and likes to wear them, despite the fact that such apparel must be specially built to hide the bulging of his football muscles.

He is physically unafraid and proved it on one of the best teams use ever had, but he cannot .stand the sight of blood. Recently, during a scene on location for Republic’s current saga, “The Fighting Sea Bees,” he complacently risked his life rather than use a double; later that afternoon, a Marine sergeant in charge of five ammunition in the area showed him a blasted arm, casualty of a recent untimely explosion.

“Why aren’t you in the hospital?” Wayne asked, averting his eyes unhappily.

“i’ve been handling the stuff for twenty years,” shrugged the sergeant, “and I’m not letting a little accident like this knock me out.” But the Duke was knocked out for the rest of the afternoon.

Used to being a family man, he is unhappy away from his family, essentially bored, somewhat indecisive, a little angry at everything and everyone. But he hides his emotions well. When we caught up with him (at Carlsbad Inn, hard by Republic’s Oceanside location camp) he was pleasantly spending a Sunday evening with some thirty off-duty Marines. Later, in the hotel’s dining room, after the regular guests had gone and only a headwaiter (sleepily wringing his hands in a corner) was left, the Duke’s party really got going with all newcomers welcome.

At one end of the room a bearded personality by the name of Abdullah, who acts as Wayne’s rubber after a hard day, stood on a flower stand, where, wrapped in a tablecloth and with a napkin on his head, he gave an aesthetic rendition of the muezzin’s call to worship; at the other end, the Duke and his chorus answered with equal feeling but slightly less aestheticism, singing verses of “Gertie From Bizerte” recently imported from North Africa.

Mr. Abdullah confided to us later that he expends most of his energy massaging away the soreness of Wayne’s right shoulder, explaining that on such occasions each Marine inevitably says good night by giving the shoulder a friendly, you-don’t-know-your-own-strength punch while adding, “You’re a good guy after all, Duke.”

His co-workers back at the studio have known that about him for years. Ask them why and they’ll talk you into a coma citing incidents. The most typical concerns a day when he had some free time from his own “Mesquiteers” picture and used it to visit the “Melody Ranch” set on the same lot. While the scene, in which a trolley car was to run out of control and smash into a brick building, was being set up, the Duke got into conversation with the stuntman who was waiting at the streetcar’s wheel.

“Wish I had time to run over to the commissary for some cigarettes,” the stuntman said.

“Go ahead,” Wayne told him. “I’ll hold this thing till you get back.” Three minutes later the director called for action. Crash! . . .

Afterwards, when the Duke had been pulled from the debris and dusted off, someone asked him why he hadn’t yelled at the director to wait. “What,” he said, “and get that guy in Dutch?”

Lancaster is a small patch of parched dwellings on the fringe of California’s Mojave desert, seventy-five miles from Los Angeles; Judy Garland spent her childhood miserably there, and so did Duke Morrison, because his father, an Iowa druggist, had been told to go West for his health. Later, having regained it, Mr. Morrison took his family to Glendale, opened another drugstore and enrolled his son in the local high school. The boy started growing out of his pants at thirteen, grew right into the football team and the Senior play, in which he played—with great verve but no talent—a duke. He jerked sodas, picked citrus fruit and was an iceman; but he wanted to go to Annapolis.

Pursuant to this end, he urged his father to contact his Congressman and secure an appointment. Mr. Morrison did his best. Young John was given a tryout and was rejected: he was no scholastic whiz. This was not a tragedy, however, since football scouts from USC had observed his brawn and tactical skill on the field and had offered him a gridiron scholarship.

He had only one year in the Varsity before he quit SC. He’d been given a job as prop-man and juicer at the old Fox studios during the summer following his sophomore year, and he ijever went back; the broken ankle suffered during scrimmage that spring represented a direct menace to his “scholarship”—after all, no football, no dough. . . .

For a year he lugged props in John Ford’s company, wherein a friendship developed between the two. Ford nudged him into a number of extra jobs on occasion, allowed him extra concessions, saw that he earned more money than the other prop boys. As a result of this favoritism, of course, John was not kept on at Fox when Ford left the company.

Then came an interlude, an adventure so thoroughly suited to the mood and character of John Wayne, in any circumstance and at any age, that it must be included here. He had gone to San Francisco with a friend, some letters of introduction to various businessmen, and eighty dollars. They presented all the letters, saw the town for two days and nights, and thereupon awoke with dark brown tastes, no money and no jobs.

John had heard that there were opportunities for football players in Honolulu. He looked up the sailings in a newspaper, had a talk with his friend: that day, when a little old lady walked up the gangplank of the Matson liner Malolo, two strapping young men (obviously grandsons or nephews, come to see her off) were close at her heels.

Twenty-four hours later they were still skulking in an empty stateroom, hungry and immensely bored. They rang for a bellhop, finally. “We’re stowaways and we’re starving,” they explained simply.

In the brig, at last, they sat down to a meal. Just before the Malolo reached Hawaii it met a small freighter headed for the mainland, in a rough sea. An exchange was made: Two stowaways for one seaman with acute appendicitis and by the week’s end the two were in San Francisco, in jail, but still eating.

Now young Mr. Wayne was in a mood to retire, to settle into something routine and predictable. Ford was once again in residence at Fox—John took his old job there and the big push was started. Raoul Walsh, it appeared, was looking for a “discovery” to play the lead in “The Big Trail” and Ford told Walsh he had just the boy for him. Walsh, meeting John on a studio street, said, “Let your hair grow—we’ll make a test,” and John did, and the test was right.

And after that Duke Morrison was in. There was the new Depression (it was 1930) ; to plug the picture Walsh dressed his find in buckskins, handed him a squirrel gun and sent him off on a personal-appearance tour as the genuine article straight from the Big Smokies. The theater audiences didn’t really get hep until he hit Chicago, where the boos began. John got a haircut and came home in great relief, to make a quickie called “Girls Demand Excitement” and something pretty awful entitled “Three Girls Lost.”

And after that Duke Morrison was out again.

The really amazing thing is that he ever got another job in Hollywood. “The Big Trail,” even with the P.A. tour thrown in, lost a sizable fortune—but it did prove that John Wayne looked fine when seated on a horse, and that he continued to look fine after the horse was in motion. In a town where a surprising number of Western stars have to be helped into a saddle, Wayne’s ability to ride represented a saving on stuntmen’s salaries.

Producer Leon Schlesinger signed him for hoss operas, in the nick of time. Eight years before, on New Year’s Eve of 1926, he had gone to a party where he had met the very pretty, very social Josephine Saenz, French-Spanish daughter of the Panamanian consul in Los Angeles. He had fallen in love with her then, and he had been courting her ever since, with such fidelity that finally, in 1934, she agreed to marry him. ‘The Schlesinger contract meant that at last he could afford her.

He was happy then, and for the next eight years, during which his two sons and two daughters were born in the rambling Italian house he had bought for them. He did not think of himself as an actor in the Hollywood sense, but as a father and husband who made a good

income by riding up and down in front of cameras. In his free time he romped with the kids, took his wife dancing, went hunting and fishing, stagged it on occasion to the fights or to a Club for a poker game.

That, in all probability, would have been the sum of his story had it not been for John Ford and a picture called “Stagecoach.”

It was Ford who persuaded Walter Wanger to make the big budget production with an unknown cowboy actor in the lead and who talked Republic into making the loan. With “Stagecoach” Hollywood and theater-goers all over America hailed him as a new star.

Eight months ago he said, “My wife’s not in Mexico for a divorce. If she were, I’d be down there on bended knees asking her to take me back.”

What you may expect of Duke Morrison during the next months is by no means clear to this particular oracle: Four children, especially when they are as appealing as Tony, Melinda, Michael and Patrick Wayne, can put awry the best laid plans for divorce.

However, it is told of John that once, during the filming of “The Spoilers,” Duke Wayne staged so convincingly a rough-and-tumble that he crashed into two process screens, a bit of overacting that cost the studio in the neighborhood of $3000. He is like that in all he does.

Aside from any other faults he may have, he has constructed one great career for himself in Hollywood and by all indications he ought to make an even better showing in the Service. At any rate, he has a thousand friends and a million fans to show for his thirty-five years. No Duke born to purple was ever so rich.

THE END

—BY HOWARD SHARPE

It is a quote.PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JANUARY 1944

No Comments